Russia and India vie for first moon landing at lunar south pole

Russia just launched its first mission to the moon in close to 50 years, firing up a new mini space race this August amid broad and growing international competition.

The Soviet Union, which collapsed in 1991, was the first nation to land a robotic spacecraft on the moon and it sent many afterward. But the launch Friday from Kazakhstan is the first lunar mission for Russia in the post-Soviet era. The mission makes a bold geopolitical statement: Though it was originally intended as a partnership, the Europe Space Agency backed out following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, has pushed ahead with a go-it-alone approach.

The latest contest is between Russia and India, though it’s possible — even likely — neither nation will win the title, given the difficulty of the challenge: first to land at the shadowy lunar south pole.

Each will try to put a crewless spacecraft on this unexplored region of the moon, where scientists believe water ice is buried within craters. The almost completely dark area will be a much tougher target than previous sites chosen by the Soviet Union, United States, and China, who have landed in bright conditions around the moon’s equator.

The ice is essentially space gold.

It could be mined for drinking water or split apart into oxygen for breathing and hydrogen for rocket fuel. Some speculate the fuel would not only be used for traditional spacecraft, but perhaps thousands of satellites that companies are putting into space for various purposes.

“We have India attempting to join a very exclusive club — only 3 countries have successfully done a soft landing on the Moon. On the other hand, we have Russia attempting to do something it has not done in nearly half a century,” Victoria Samson, a space policy expert at Secure World Foundation, told Mashable. “Fascinating that it (a former leader in civil space) is striving to keep up with India, whose space program is much younger.”

First country to land at the moon’s south pole

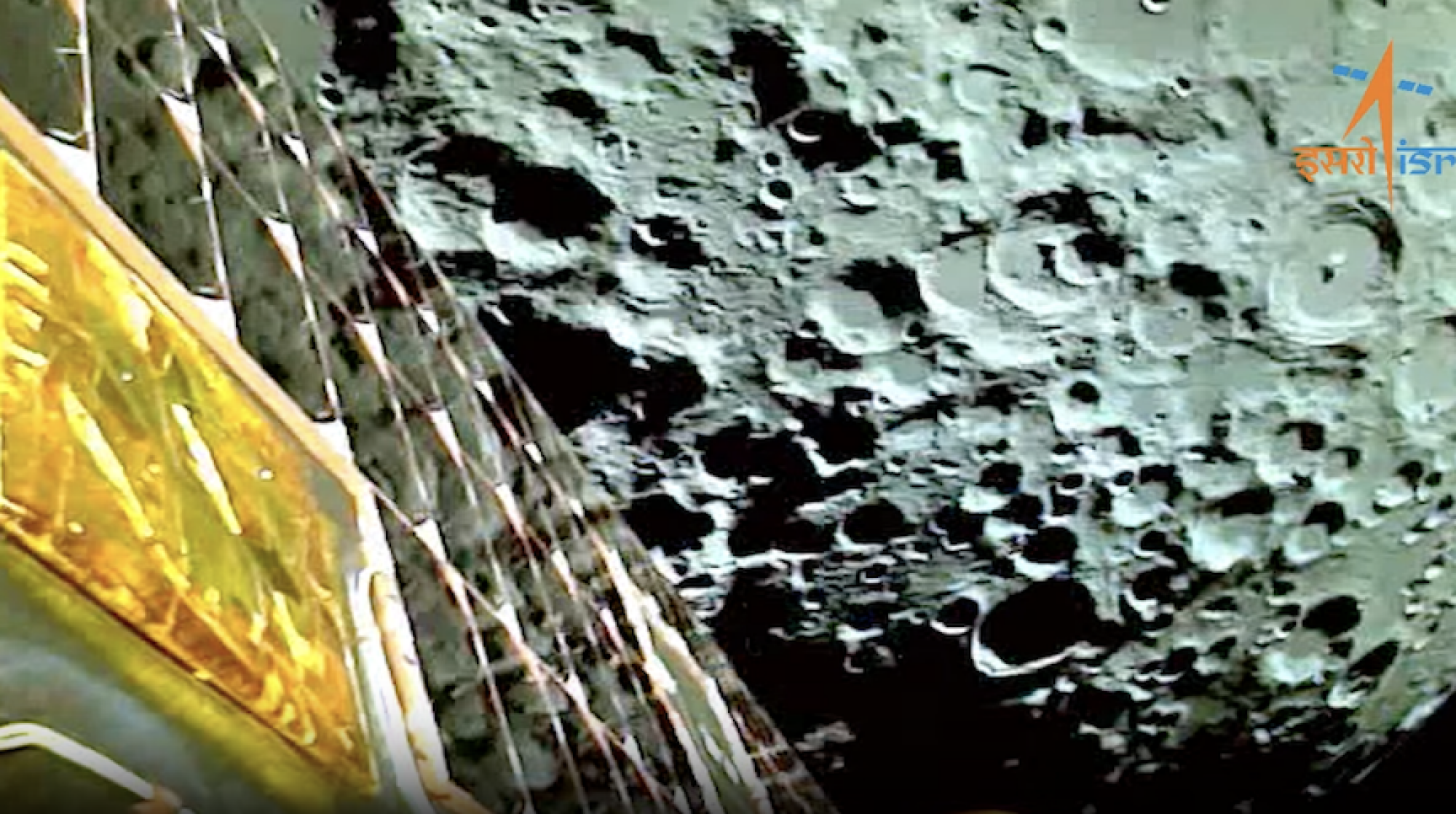

The Indian Space Research Organization’s Chandrayaan-3 mission launched in mid-July from Sriharikota, a barrier island of southeastern India. It’s the space agency’s do-over following a crash on the moon in 2019. The team will get its next crack at a moon landing Aug. 23. Roscosmos, on the other hand, has said its robotic Luna-25 spacecraft, which lifted off from the Vostochny spaceport, could touch down on the moon as early as Aug. 21.

Meanwhile, Japan’s space agency is also close to liftoff this month. Though it is not planning to go to the brutal polar region, it is among the many countries and private ventures rushing to get to the moon this year. The mission is expected to launch from the Tanegashima Space Center in Japan on Aug. 26.

Though 60 years have passed since the first robotic moon landings, touching down safely remains a daunting task, with less than half of all missions succeeding. Unlike around Earth, the moon’s atmosphere is very thin, providing virtually no drag to slow a spacecraft down as it approaches the ground. Furthermore, there are no GPS systems on the moon to help guide a craft to its landing spot. Engineers have to compensate for these shortcomings from 239,000 miles away.

One need not look further in history than this April for a reminder of that difficulty. Private Japanese startup ispace failed to land on the moon after its spacecraft ran out of fuel during descent and crashed.

The valuable lunar resources are what’s driving the renewed interest in Earth’s satellite. If toting heavy fuel on rockets — which require extreme amounts of propulsion to break free of gravity —can be avoided, that could save space-faring countries and companies a fortune in space travel costs in the future. It also means the moon could become something akin to a cosmic gas station. Lunar water alone could be a $ 206 billion industry over the next 30 years, according to Watts, Griffis, and McOuat, a geological and mining consulting firm.

“This is what we need to prove,” Brad Jolliff, director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, told Mashable last fall. “The business case is that it’s actually less expensive to develop the resources on the moon as opposed to launching them from Earth.”

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Light Speed newsletter today.

Why NASA’s going back to the moon

Many upcoming missions will set the stage for NASA‘s own lunar ambitions, shipping supplies and experiments to the moon’s surface ahead of astronauts’ arrival on Artemis III, as well as kickstarting a future economy in and around the moon. That’s largely thanks to the U.S. space agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services Program, established in 2018 to recruit the private sector to help deliver its cargo.

Landing in the south pole is but one challenge in the emerging modern space race. As of late, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, a former astronaut and U.S. senator, has spoken candidly about competition from other spacefarers, something the agency has avoided in past decades. It isn’t Russia that gives him pause, but China, which is using space tactics many see as reminiscent of the Cold War era.

Russia, he has said, isn’t close to sending cosmonauts to the moon any time soon. The same can’t be said for China’s military-run space program, with plans to land people at the lunar south pole in 2030. NASA’s Artemis III mission is hoping for a late 2025 landing.

“They’re aggressive, they’re good, and they’re secretive,” Nelson told U.S. House budget leaders this April.

“They’re aggressive, they’re good, and they’re secretive.”

Talking about the situation in such terms of us-versus-them could condemn us to repeat global tensions of the past, Samson says.

“It’s wild that we have seen such a huge shift in how NASA views China,” she said, pointing out it was only a little more than a decade ago that former NASA administrator Charles Bolden Jr. wanted China to get involved in the International Space Station — that is, before Congress intervened. Now Nelson speaks openly about China as being a bad actor in space.

NASA admits to space race with China

During an Artemis program update this week, Nelson elaborated on his concerns about China. He gave an example of what he perceives as the country’s modus operandi: China’s military claimed the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea and built a runway there.

Meanwhile, India and about two dozen other countries have joined the Artemis Accords, a U.S.-led international agreement establishing standards for safe and collaborative space exploration. Russia seems to be aligning with China, which has been excluded from working with NASA by federal law. The Wolf Amendment was established in 2011 because of concerns China could exploit U.S. technology to enhance its ballistic missiles.

“If indeed we find water in abundance (on the moon), that could be utilized for future crews and spacecraft,” Nelson told reporters Tuesday. “We want to make sure that that’s available to all, not just the one that’s claiming it.”

There are new actors in this space race, but the implications have a familiar ring.

Congressman Ben Cline, a Republican from Virginia, made that all but clear this spring.

“We didn’t cooperate with the Soviet Union back in the ’60s during the space race,” he told Nelson during a committee hearing. “I don’t think it’d be wise to cooperate with the Chinese now.”