Solar eclipses were once extremely terrifying events, experts say

When the Aztecs experienced a total solar eclipse, the wailing began.

After all, the moon had eclipsed the almighty sun, transforming it into an ominous onyx eye.

Then there were a tumult and disorder. All were disquieted, unnerved, frightened. There was weeping. The common folk raised a cry, lifting their voices, making a great din, calling out, shrieking. There was shouting everywhere.

These are translations from the early ethnographer Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, a friar who meticulously recorded Aztec culture and history in the 1500s. Human sacrifices ensued, Sahagún noted, an attempt to feed the sun invaluable energy from these bodies.

And in all the temples there was the singing of fitting chants; there was an uproar; there were war cries. It was thus said: “If the eclipse of the sun is complete, it will be dark forever! The demons of darkness will come down; they will eat men.”

Not all cultures feared eclipses. Some, like the Navajo, viewed an eclipse as a time for reflection and renewal. But fear was awfully common across the globe. It’s an understandable sentiment; for those today who stand in the shadow of a rare solar eclipse — like the many millions with the chance on April 8, 2024 — the exciting experience can also feel awfully strange, if not disquieting. A constant in our lives, our radiant star, turns black and reveals its ghostly corona, or atmosphere.

“It was profoundly unsettling to have this black hole in the sky,” Melissa Barden Dowling, a Roman historian at Southern Methodist University, told Mashable. “Losing the sun would be just terrifying.”

For many peoples, a total solar eclipse was profoundly terrifying because they believed in an animate universe where earthly or cosmic happenings were divine communication (these common worldviews existed in places like ancient China, India, Mesoamerica, the Mediterranean, and beyond). “It was rooted in the idea that the gods spoke to us through the natural world,” Dowling said.

There is one long-lived culture that has a notable absence of solar eclipse accounts in its widespread art and text: ancient Egypt. This surprises Dowling, yet it’s telling. Mind you, this was a society that for thousands of years worshiped the falcon-headed sun god, Ra, who was considered a divine father of many pharaohs. But in ancient Egypt there was a general avoidance of the eclipsed sun. “There’s no serious attempt to record solar eclipses in the material that survived,” Dowling noted.

A plausible reason? “It was too dangerous to depict,” she said.

The demons of darkness will come down; they will eat men.

It’s difficult to know what every culture thought of such a dramatic event. But descriptions often weren’t rosy. Thousands of years ago, in 1200 B.C.E., scribes in Anyang, China, recorded solar eclipse events on bones. “The Sun has been eaten,” they wrote.

Following a total solar eclipse, prominent Aztec warriors would hold all-night vigils. They quaffed maize beer, explained Adam Herring, a historian at Southern Methodist University specializing in the pre-Columbian Americas. The warriors grew drunk with their military brethren. “They showed solidarity for the greatest of all warriors, the sun god, in his time of need,” Herring said.

Indeed, the Aztec sun god was often beset with threats in the darkness, when malevolent gods would come out. It’s one reason why Aztecs would sacrifice human lives — to release energy from bodies and offer them to the sun god. A total eclipse, however, unleashed perhaps the greatest of cosmic struggles for the sun god, as the deity’s resplendence was extinguished in broad daylight.

It’s little surprise advanced cultures like the Aztecs were suspicious of the dark, like pre-Industrial cultures around the world. In Western folklore, the deepest of night, the “witching hour,” is when evil beings gather their strength and lurk among us.

“Nighttime is a very troubling time,” Herring said. “It’s cold, dark, and dangerous.” Especially when it strikes unexpectedly.

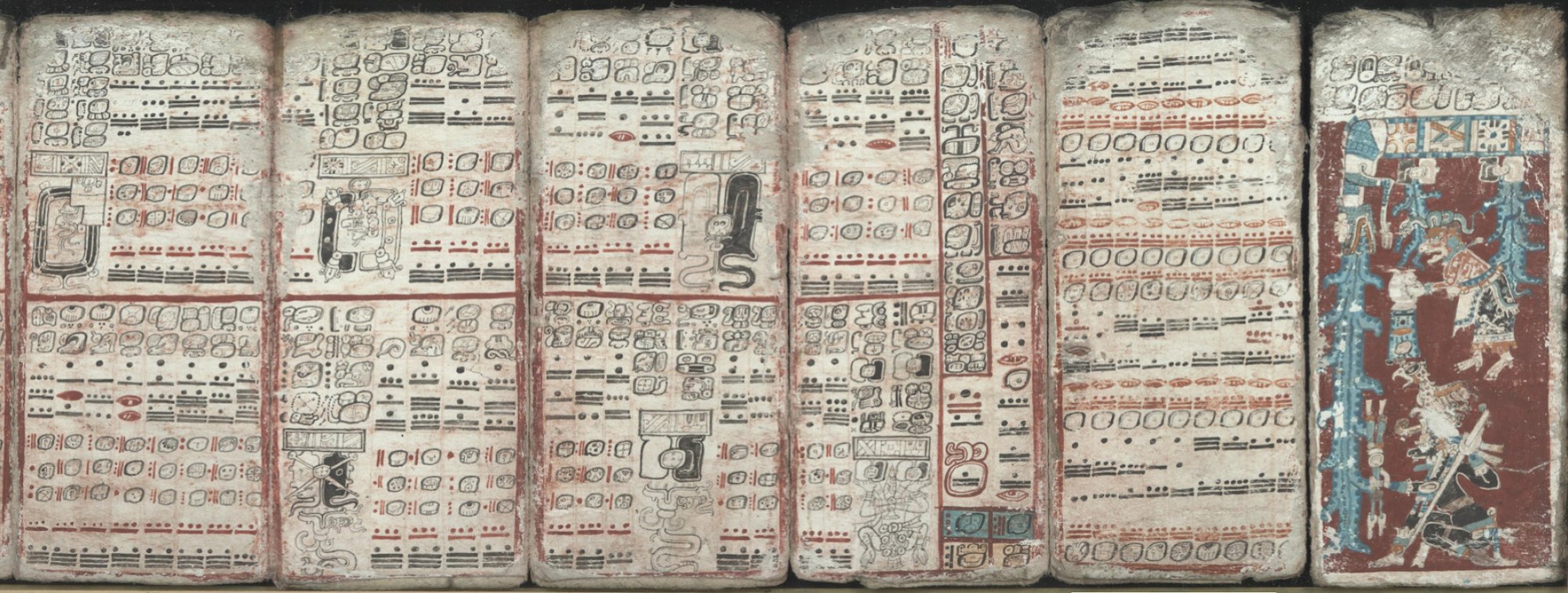

Yet even knowing a solar eclipse is coming doesn’t smother the fear. The Maya devised intricate eclipse tables, showing when an eclipse was possible. “That was worked out with incredible intricacy and ingenuity and persistent, dogged observation over centuries,” Herring marveled. The Maya even predicted an eclipse that happened in July 1991, many centuries in advance.

Still, the Maya dreaded totality. “They were feared events viewed and based on the Maya cosmovision as the struggle of the Sun and the Moon, day and night, or the good and the bad,” explained the Heritage Education Network Belize, an organization preserving Belizean history and culture. “This phenomena was seen as a bad omen, but also as a closure and as a sign of renewal.”

It’s cold, dark, and dangerous.

As humanity’s space and astronomical knowledge evolved, eclipses have grown less ominous — though not completely so. During the 2017 total solar eclipse, among gasps I heard unsettled cries across the high Oregon desert. In her seminal 1982 essay Total Eclipse, Annie Dillard reported hearing rattled people staring up at the eclipsed sun. “From all the hills came screams,” she wrote.

By the 1800s, the astronomers made it widely known that these eclipses were caused by an enthralling, though not dreadful, cosmic dance. Take this excerpt from the Mexican publication La voz de la religión, on July 24, 1852, before such an eclipse:

The total eclipse is also a spectacle that deserves to call anyone’s attention… it looks like the unraveling of nature’s well-arranged order… [But] it is possible to calculate with the greatest precision the movements of celestial bodies. Now, eclipses, far from scaring people, have become for them an object of curiosity.

Times had turned. “The mood changes from fear to curiosity,” Amílcar E. Challú, a historian of Mexico and Latin America at Bowling Green State University who translated both the quote above and that at the start of this article, told Mashable.

Later, in 1908, The Mexican Herald gave recommendations to readers for how to witness a looming total eclipse. Some 500 people would take a train an hour north from Mexico City to experience the event, Challú, who hosts the podcast Eclipsing History, explained.

In modern day, eclipse chasers travel all over Earth to catch these cosmic spectacles. And on April 8, 2024, people will drive or fly hundreds to thousands of miles to peer at the dark star.

It’s worth it. “It’s most fun to experience with other people, because of the surprise, and the awe,” the Roman historian Dowling said.

But it might be a bit unsettling, too. We’re still human, after all.