‘Telemarketers’ review: A scam you need to see to believe

If you’ve ever been called by a pushy telemarketer, chances are you’re frothing at the mouth to see these scammy nuisances get their comeuppance. That’s the initial promise of HBO’s docuseries Telemarketers, which dives into the madcap world of telemarketing firm Civic Development Group (CDG).

However, what starts as a look at CDG’s bizarro environment soon morphs into a deeper investigation of a major scam, shifting focus from the telemarketers manning CDG’s phones to the higher-ups looking to profit by any means possible. Telemarketers frames this investigation as a scrappy buddy comedy, with two former CDG employees hoping to take down the industry with their findings. The result — part guerilla exposé, part offbeat character study — is easily one of the wildest true crime stories you’ll see this year.

What is Telemarketers about?

Telemarketers kicks off in the early 2000s, when high school dropout Sam Lipman-Stern (who co-directs Telemarketers along with Adam Bhala Lough) accepted a telemarketing job at CDG. There, he and his co-workers — many of them convicts recruited from halfway houses — worked to raise money for charitable organizations, most of them police charities such as state and local lodges of the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP).

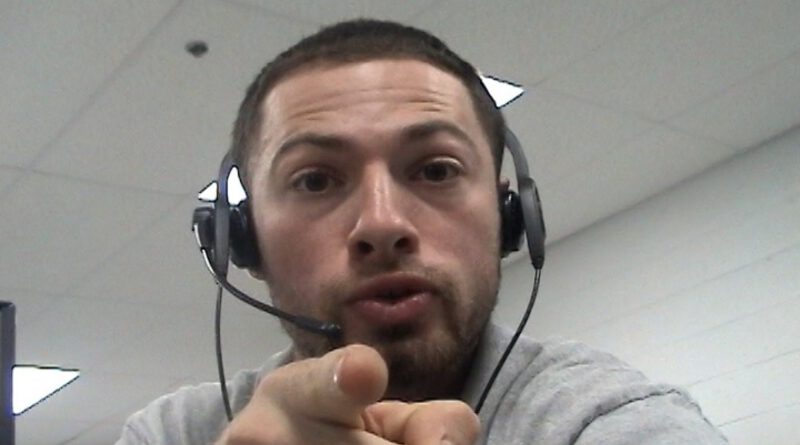

For Lipman-Stern and his fellow CDG telemarketers, the work came second to the workplace, which was, as one employee describes it, “a fun place to be.” Staff hooked up in CDG bathrooms, smoked and drank on the job, and even gave themselves tattoos while working. The office was so chaotic that Lipman-Stern began recording the telemarketers’ hijinks and posting them to YouTube, where people could witness for themselves the scenes of debauchery playing out against a bleak corporate background. Still, CDG managers didn’t care about how workers behaved, so long as they made enough money.

While the in-office heroin and sex are pretty crazy on their own, the true madness of CDG lies in its money-making methods and supposed charitable work. First off, only 10 percent of donations actually went to charitable organizations, most of which were FOP-related. In exchange for their donations, donors would receive special “friend of the FOP” decals to put on their cars or in their business windows, the presumption being that a cop would be less likely to pull them over if they saw one.

The telemarketing tactics themselves range from aggressive to downright predatory. Rebuttals for almost every argument against donating are hung up around office cubicles for telemarketers to remember. CDG workers will re-target people, especially the elderly, in order to make more money. (One non-CDG telemarketer admits to getting $ 82,000 from an elderly man over four months.) And while telemarketers are not allowed to pretend to be cops seeking donations, that doesn’t stop them from putting on a “cop voice” so they sound like a cop.

CDG’s approach eventually led to them getting shut down, but by then, they’d already “re-invented American telemarketing,” as Telemarketers tells it. Similar tactics persist today, even escalating the game with automated calls that use dead telemarketers’ voices. And guess who’s still involved? The FOP. The question Telemarketers poses becomes: were they unwitting bystanders, or are they the real scammers?

Telemarketers puts together a ragtag investigation

To get to the bottom of these telemarketing scams, Lipman-Stern teams up with his CDG coworker Patrick J. Pespas, credited in the series as a “telemarketing legend.” Sporting a mustache and a squeaky voice, Pespas is an immediately arresting character. He insists Sam film him snorting heroin early in the series, and he’ll even show up so high to work that he nods off at his desk. (That won’t stop him from making a sale though.)

Telemarketers is just as invested in Pespas as it is in the actual telemarketing scams, examining his attempts to get sober and his relationship with his wife. This focus on Pat provides Telemarketers with a much-needed emotional throughline as he and Lipman-Stern embark on their journey to document the wrongdoings of the telemarketing industry.

The first stages of Lipman-Stern and Pespas’ investigation get off to a ragtag start, just the two of them and a camera against the world. After an early interview, Lipman-Stern wonders if Pespas “might suck at this,” and you realize you’re watching two amateurs learn to be documentarians on the fly. That realization lends to Telemarketers‘ charm and authenticity, along with Pespas’ passionate (if not always accurate) lines of questioning.

Once their investigation kicks back up in 2020 after a long hiatus, the documentary gains some polish thanks to Lipman-Stern’s increased experience and Bhala Lough’s involvement. These more recently shot sections result in some of Telemarketers’ most disturbing sequences, including one where one of the callers venomously wishes death on everyone who hangs up on him.

Telemarketers certainly isn’t perfect. Some cliffhangers have little-to-no payoff, while other questions deserve more examination. Still, this three-part docuseries will no doubt scratch your itch for stories of scammers getting called out, all while giving you unique whistleblowers to root for in Lipman-Stern and Pespas.

New episodes of Telemarketers air Sundays at 9 p.m. on HBO and Max.