The most spectacular images of Venus ever captured

Long ago Venus was nicknamed Earth’s twin, a world roughly the same size as our home planet and the nearest neighbor in space.

But as scientists have learned more about the toxic world, Venus has received a reputation as the evil sibling — a hellscape, where the thick atmosphere traps heat in a runaway greenhouse effect, making it the hottest planet in the solar system, despite its being farther than Mercury from the sun.

This bizarro world, with surface temperatures about 900 degrees Fahrenheit, spins quite slowly in the opposite direction of Earth, with the sun rising in the west and setting in the east. A Venusian day is actually longer than its year. The whirling clouds rain sulfuric acid, and the planet has the most volcanoes in the solar system, according to NASA. An astronomer recently discovered a volcanic eruption there, evidence that, however inhospitable, the planet is still geologically active.

Venus might once have been an ocean world capable of life, but that would have been a billion years ago. Scientists want to learn how Venus evolved into Earth’s alter ego. Studying the planet hasn’t been easy, though.

Take a look at some of the best images captured of Venus, some mere moments before the camera fried.

NASA solar probe swings by for Venus photo-op

The Parker Solar Probe, which studies the sun, caught rare images of Venus’ nightside during a brief encounter in February 2021.

The dark area shown is a massive highlands region called Aphrodite Terra, extending about two-thirds of the way around the planet. Because of its elevation, it’s cooler and therefore darker. Scientists also think the light rim around the planet could be “nightglow,” a phenomenon caused when interacting atmospheric particles give off light during the night.

Though the probe’s focus is the sun, Venus is important to the mission, too. The robotic spacecraft will fly by Venus seven times throughout its journey, using the planet’s gravity to bend its orbit. These maneuvers give Parker the oomph to fly ever-closer to the sun on its quest to study solar wind, the source of space weather, and its origins.

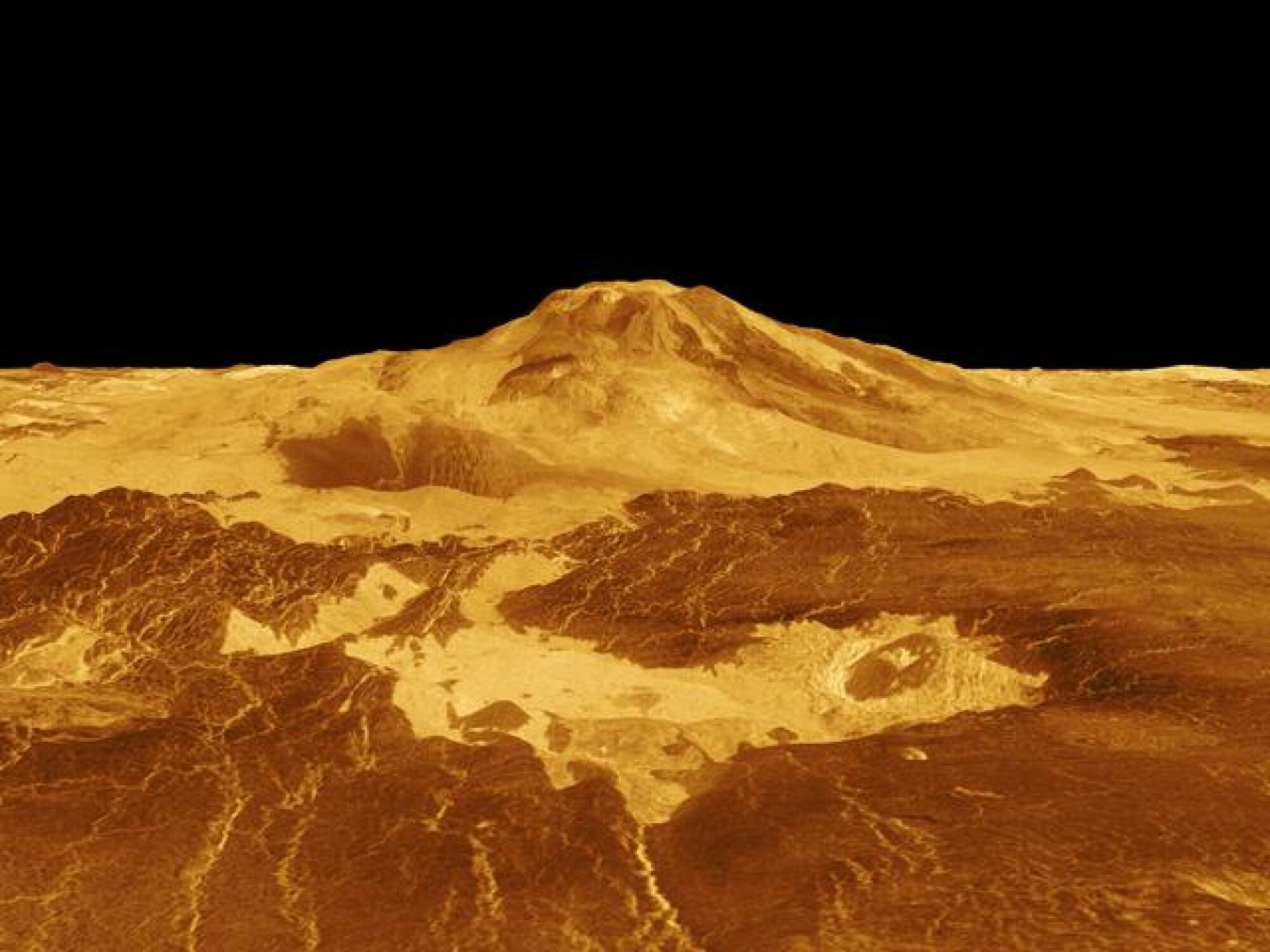

Scientist discovers volcano still erupts on Venus

A research professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks looked through 30 years of old NASA Magellan mission images to find evidence of volcanic activity. Eventually, he found a needle in a haystack.

Within the archives, Robert Herrick discovered one volcano had a vent that had doubled in size and changed shape over eight months in 1991 — telltale signs it had erupted — making this 3D image of the Maat Mons volcano even more intriguing.

Herrick spotted a lava lake in Atla Regio, a vast highland near Venus’ equator with volcanoes Ozza Mons and Maat Mons. Planetary scientists have long-suspected the region to be volcanically active, according to NASA, but there has been no direct evidence until now.

Active volcanoes help scientists understand the impact a planet’s interior has in shaping its crust, forging continents and mountains, and potentially helping life to emerge. One of NASA’s upcoming missions to Venus will delve deeply into this research. Within a decade, the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory hopes to lead VERITAS — short for Venus Emissivity, Radio science, InSAR, Topography, And Spectroscopy — to study the rocky planet from surface to core.

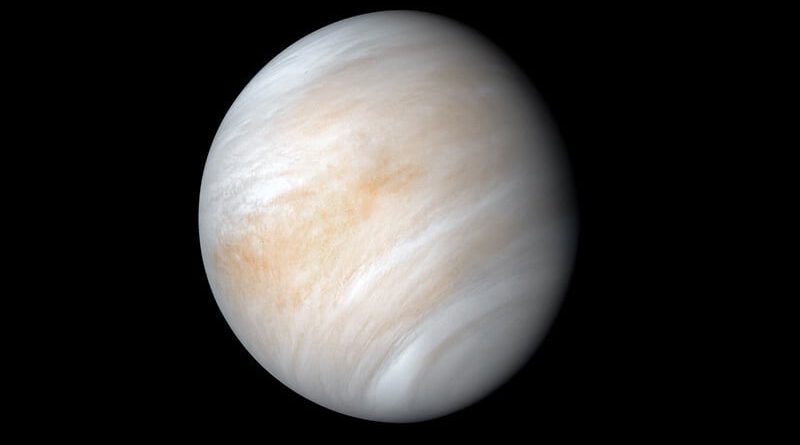

Magellan mission made first global map of Venus

Despite NASA’s Magellan mission having arrived at Venus over 30 years ago, its legacy continues. The spacecraft made the first global map of the planet’s surface, one of the most famous portraits of Venus ever created.

This image used Magellan’s radar to stitch together a global mosaic. NASA filled in missing data with information from the Pioneer Venus Orbiter. The colors were selected based on those captured by the Soviet Union’s surface missions to Venus in the 1970s and ’80s.

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Light Speed newsletter today.

Magellan was responsible for surprising discoveries about Venus, including that lava may have resurfaced the entire planet in its relatively recent past. The mission ended in October 1994 when the spacecraft intentionally crashed into the planet’s surface.

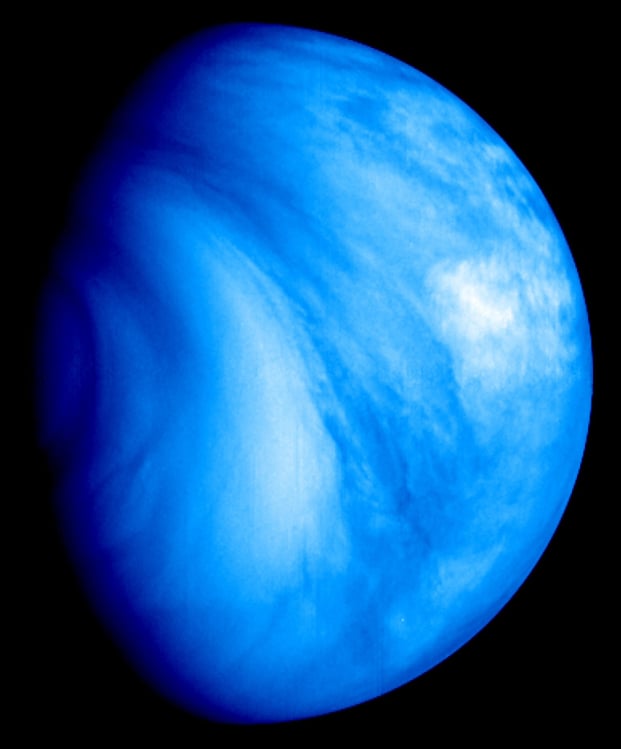

Venusian clouds move faster than Cat-5 hurricane

Most people wouldn’t expect to see Venus in an almost Earth-like shade of blue, but this is the planet in false-color ultraviolet wavelengths. In this light, the European Space Agency’s Venus Express mission captured the details of the planet’s mysterious clouds over the southern hemisphere in July 2007.

ESA wasn’t the first to do something like this: NASA’s Galileo spacecraft observed Venus’ clouds about 1.7 million miles from the planet in February 1990. The above image, however, shows the planet’s southern hemisphere from a distance of 22,000 miles from the surface.

On Venus, hurricane-force winds blast miles-thick clouds around the planet. While the planet slowly rotates on its axis, completing one revolution in 243 Earth days, its clouds move at a dizzyingly faster pace, spinning around the planet in just four days. What’s more, the mission discovered that the planet’s rotation is slowing down, while its clouds are speeding up.

Venus crosses in front of the sun during rare event

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory mission snapped photos of Venus as it moved across the face of the early morning sun on June 5, 2012, in an astronomical event known as the transit of Venus. The next such transit will not happen until 2117, according to the space agency.

The transit of Venus first got attention in the 18th century, when the distance of planets wasn’t yet known. Astronomer Edmund Halley realized by observing the transit from different spaced-out spots on Earth, scientists should be able to triangulate the distance to Venus.

The planet’s crossing is extremely rare, coming in pairs separated by more than a century.

Japanese orbiter Akatsuki studies Venus’ climate

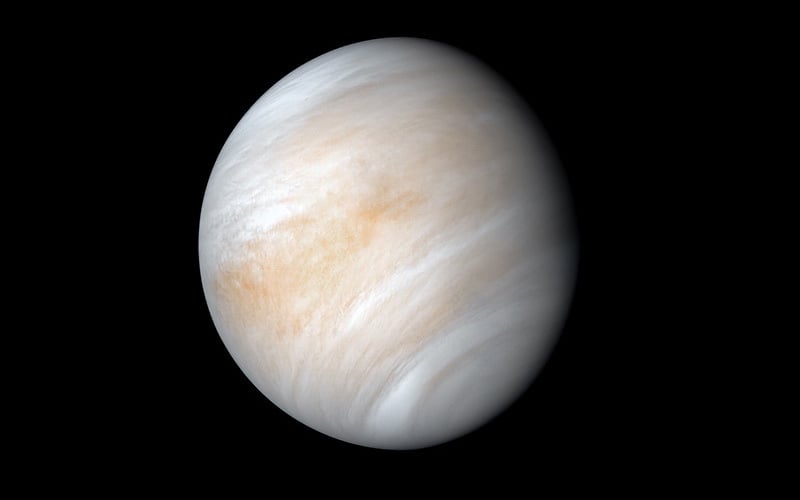

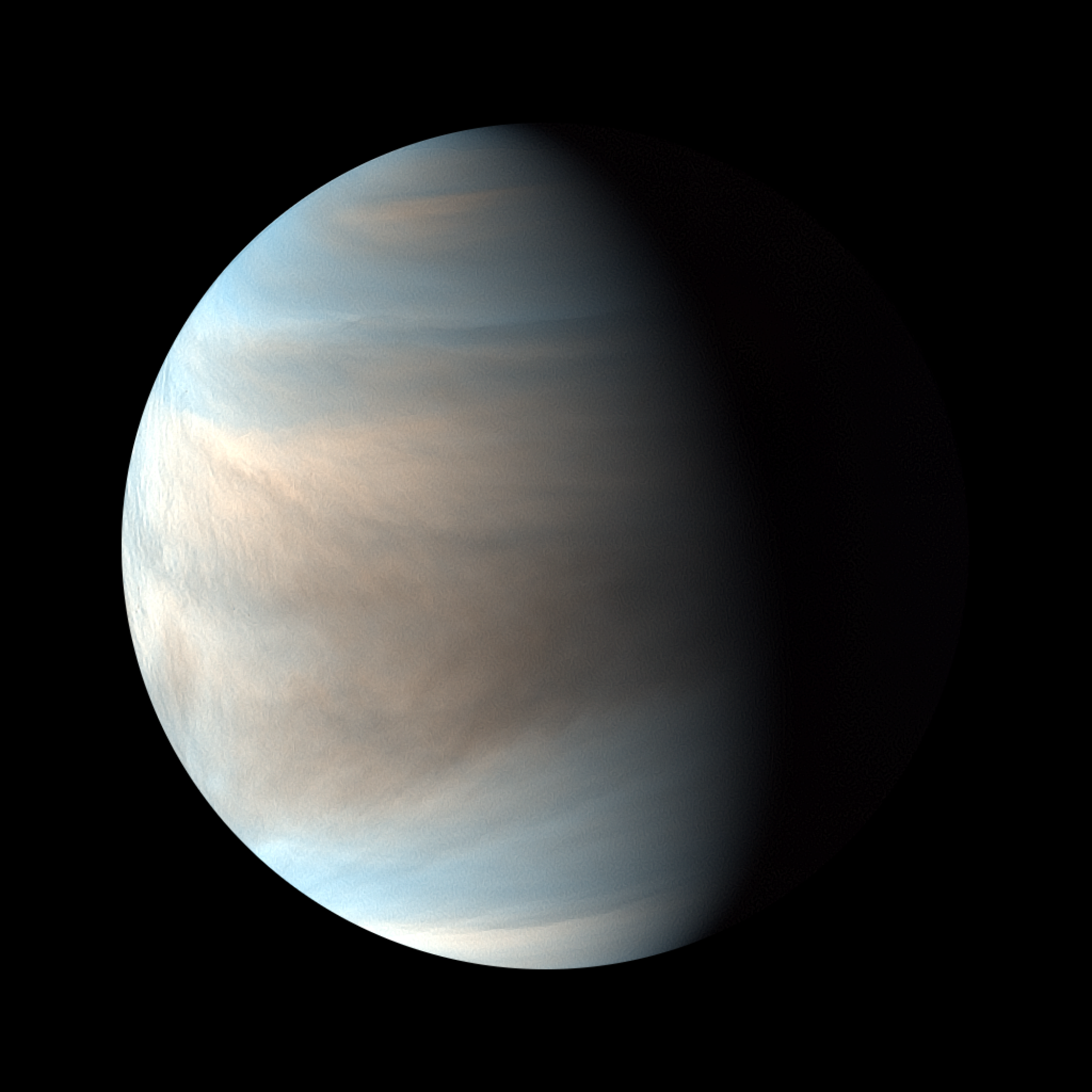

This serene view of Venus came from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Akatsuki spacecraft, the nation’s first successful mission to explore another planet.

Launched in 2010, the JAXA spacecraft missed its mark and didn’t insert into Venus’ orbit until 2015. Since then, the mission, sometimes known as Planet-C or Venus Climate Orbiter, has bounced back, studying weather patterns, trying to confirm lightning among the clouds, and searching for signs of active volcanoes.

In this ultraviolet image of the planet’s atmosphere from orbit, which uses false color, sulfur dioxide causes some clouds to look dark because of sunlight absorption.

Soviets took the only photos from Venus’ surface

These might not be the most glamorous images of Venus, but they represent a historic achievement. The Soviet Union was — and remains — the only nation ever to try landing on the planet’s surface.

It took several attempts, but the Venera 9 and 10 spacecraft succeeded in landing and surviving on the planet long enough to send back images in 1975. Two later missions, Venera 13 and 14, also landed in 1982, sending back color images.

The challenge of landing on Venus is extraordinary: Its climate is hot enough to melt lead and the atmospheric pressure is 75 times that of Earth. All the Soviet spacecraft eventually fried in the heat, within 23 minutes to two hours after arriving, but they captured the barren, rocky landscape.

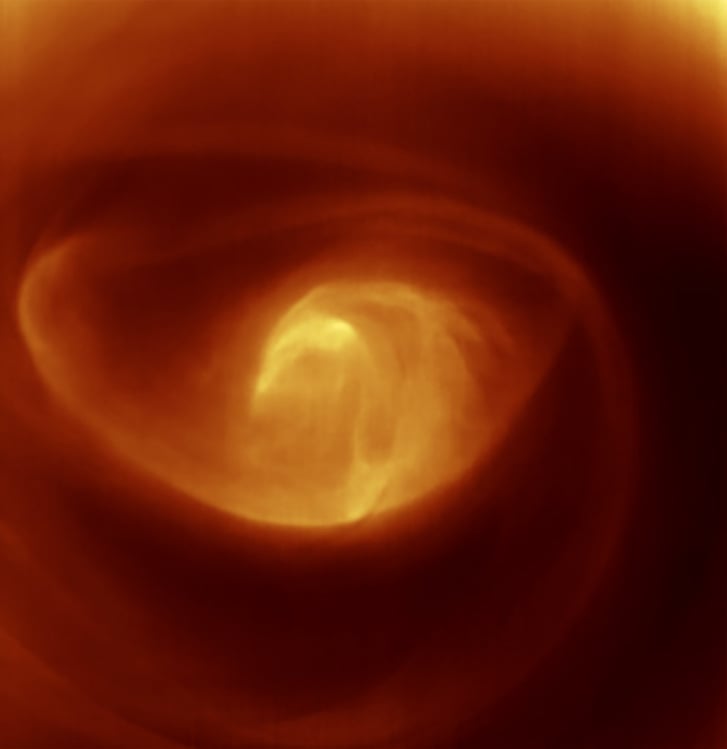

European spacecraft gets long look at polar vortex

The Pioneer Venus orbiter spotted a huge hourglass-shape depression in the clouds, some 1,200 miles wide, at the north pole of Venus in 1979. But the planet’s south pole largely remained a mystery to astronomers until Europe’s Venus Express came along.

A vortex can form when heated air from the equatorial region, carried by fast wind, spirals toward a pole. As the air converges on the pole and then sinks, it creates a phenomenon similar to the way water swirls around a bathtub drain.

The above image, captured by Venus Express in 2007, shows the southern polar vortex in detail. Over several observations, the orbiter discovered the vortex changes its shape daily. This swirl of gas and cloud is about 37 miles above the planet’s surface.