Webb telescope makes unexpected find in outskirts of our solar system

In our solar system’s proverbial “no man’s land,” a deep space realm beyond the planets, scientists detected unexpected activity.

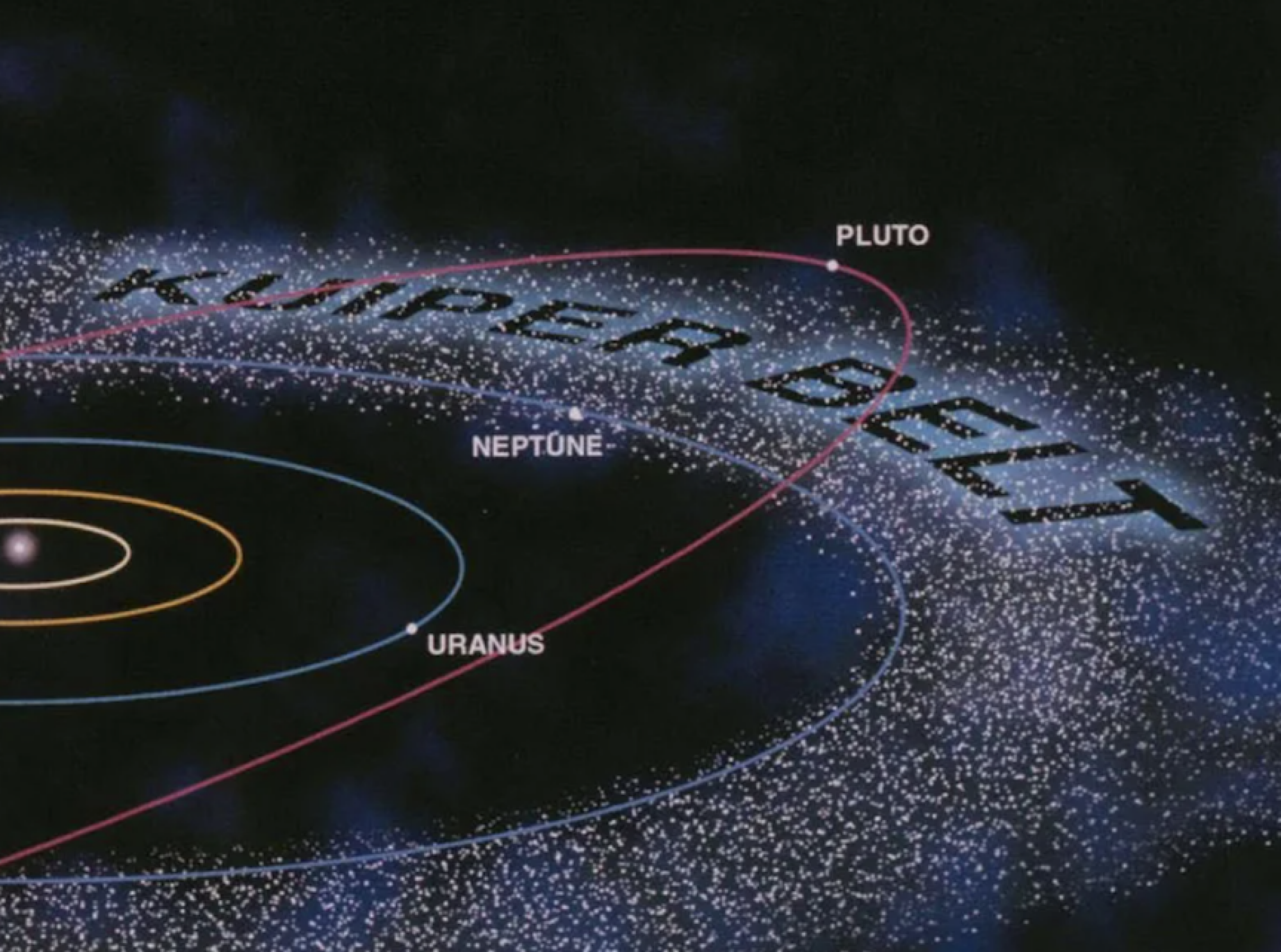

This remote area, inhabited by ice-clad worlds like Pluto (a dwarf planet), is called the Kuiper Belt, a donut-shaped region surrounding much of our solar system. It’s a relatively little known place, but millions of frozen, “dead” objects are thought to orbit there. Now, astronomers pointed the powerful James Webb Space Telescope at some of these icy objects, and found evidence that they’re not so dead after all.

“We see some interesting signs of hot times in cool places,” Christopher Glein, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute who researches icy worlds, said in a statement.

Glein, who previously conducted research into Saturn’s geyser-shooting moon, Enceladus, led this new investigation into the Kuiper Belt objects, which was published in the planetary science journal Icarus.

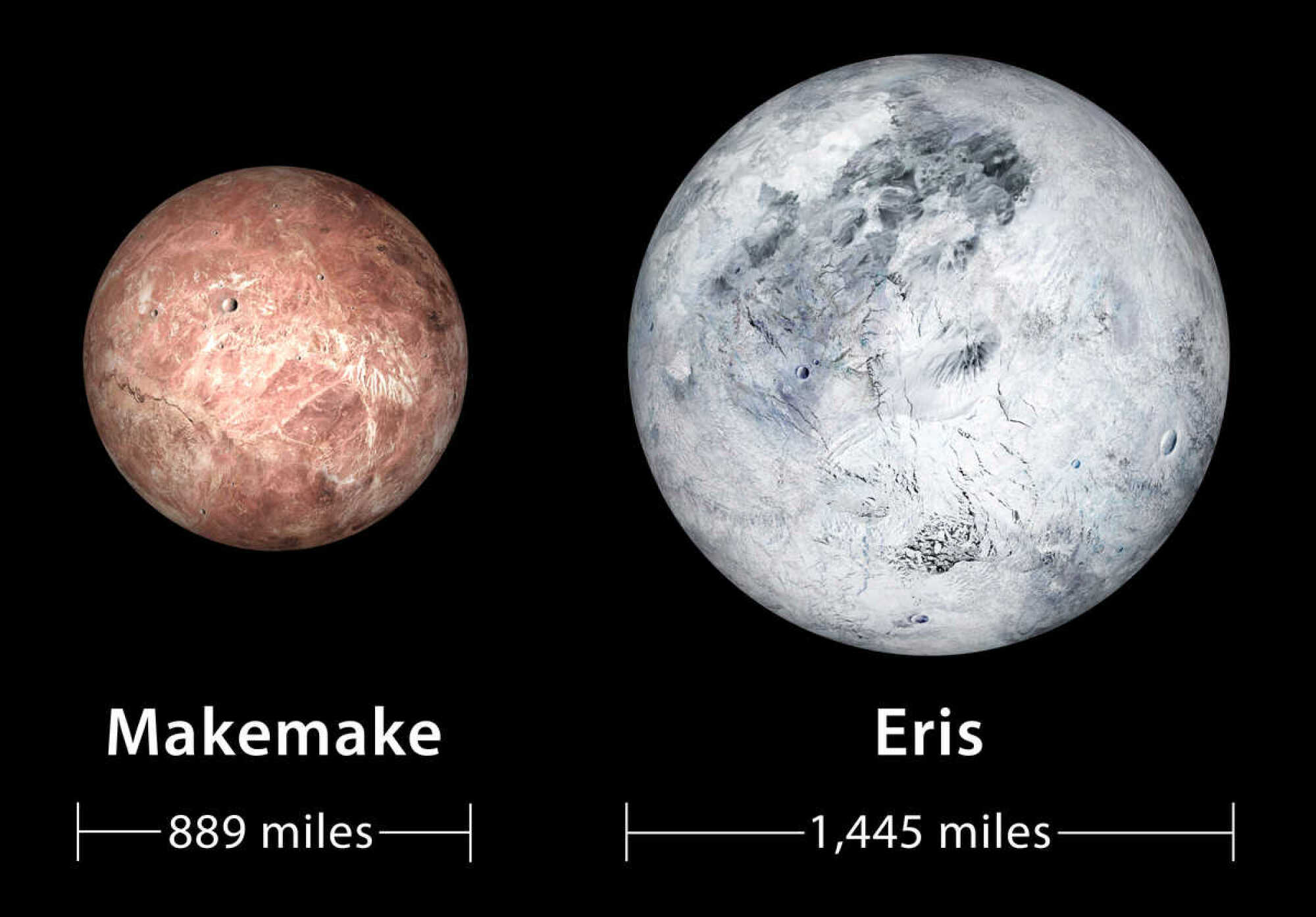

The scientists trained the Webb telescope, which orbits 1 million miles from Earth, on the two largest-known Kuiper Belt objects — Eris and Makemake. This instrument is fitted with specialized cameras that can detect different types of elements or molecules (like water or carbon dioxide) on distant worlds.

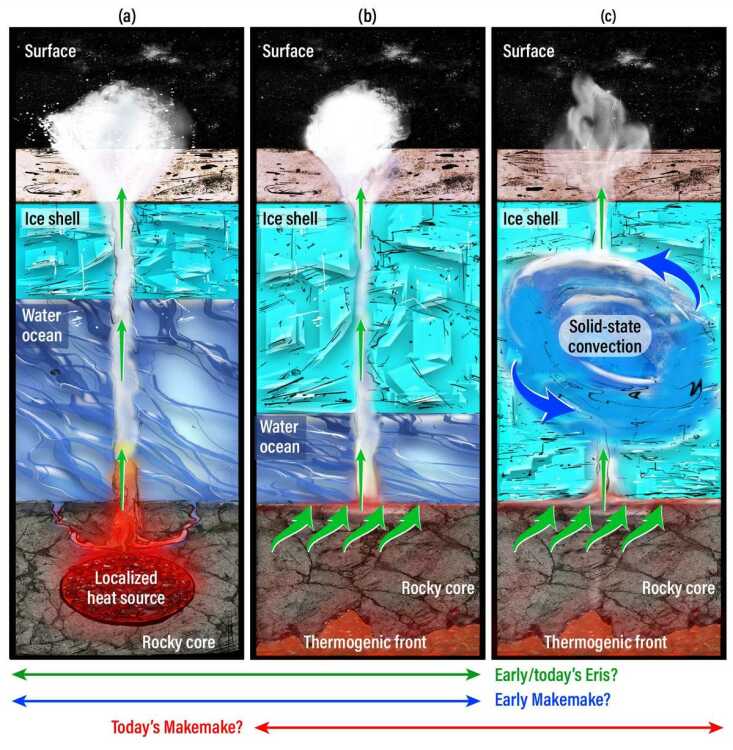

What they found was a surprise: The icy orbs and objects of the Kuiper Belt are thought to be preserved, primordial relics of the early solar system. But the frozen methane identified on the surfaces of Eris and Makemake (respectively located, on average, well over 6 and 4 billion miles away) show these molecules were more recently “cooked up,” Glein explained. This suggests hot interiors beneath these icy crusts, capable of propelling liquid or gas onto the surface. The relatively recent methane deposits also suggest that these worlds could potentially even harbor oceans, as shown in the graphic below (similar to icy moons like Europa, which orbits Jupiter).

“Hot cores could also point to potential sources of liquid water beneath their icy surfaces,” Glein explained.

It’s even in the realm of possibility that some of these frozen worlds — billions of miles away — could harbor conditions suitable for life to potentially develop — though there’s certainly no evidence of that yet.

Perhaps a mission to these cosmic frontiers is due. After all, NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto (and beyond) revealed a complex world with a diverse topography, including glaciers and mountains made of water ice.

“After the New Horizons flyby of the Pluto system, and with this discovery, the Kuiper Belt is turning out to be much more alive in terms of hosting dynamic worlds than we would have imagined,” said Glein. “It’s not too early to start thinking about sending a spacecraft to fly by another one of these bodies to place the JWST data into a geologic context. I believe that we will be stunned by the wonders that await!”

The Webb telescope’s powerful abilities

The Webb telescope — a scientific collaboration between NASA, the ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency — is designed to peer into the deepest cosmos and reveal new insights about the early universe. But it’s also peering at intriguing planets in our galaxy, along with the planets and moons in our solar system.

Here’s how Webb is achieving unparalleled feats, and likely will for decades:

– Giant mirror: Webb’s mirror, which captures light, is over 21 feet across. That’s over two-and-a-half times larger than the Hubble Space Telescope’s mirror. Capturing more light allows Webb to see more distant, ancient objects. As described above, the telescope is peering at stars and galaxies that formed over 13 billion years ago, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

“We’re going to see the very first stars and galaxies that ever formed,” Jean Creighton, an astronomer and the director of the Manfred Olson Planetarium at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, told Mashable in 2021.

– Infrared view: Unlike Hubble, which largely views light that’s visible to us, Webb is primarily an infrared telescope, meaning it views light in the infrared spectrum. This allows us to see far more of the universe. Infrared has longer wavelengths than visible light, so the light waves more efficiently slip through cosmic clouds; the light doesn’t as often collide with and get scattered by these densely packed particles. Ultimately, Webb’s infrared eyesight can penetrate places Hubble can’t.

“It lifts the veil,” said Creighton.

– Peering into distant exoplanets: The Webb telescope carries specialized equipment called spectrographs that will revolutionize our understanding of these far-off worlds. The instruments can decipher what molecules (such as water, carbon dioxide, and methane) exist in the atmospheres of distant exoplanets — be they gas giants or smaller rocky worlds. Webb will look at exoplanets in the Milky Way galaxy. Who knows what we’ll find?

“We might learn things we never thought about,” Mercedes López-Morales, an exoplanet researcher and astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics-Harvard & Smithsonian, told Mashable in 2021.

Already, astronomers have successfully found intriguing chemical reactions on a planet 700 light-years away, and as described above, the observatory has started looking at one of the most anticipated places in the cosmos: the rocky, Earth-sized planets of the TRAPPIST solar system.